Gene therapy experiment treats rare childhood blindness

Health Reporter

Moorefield Hospital

Moorefield HospitalDoctors at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London said an experimental trial of gene therapy helped four young children (born in one of the worst childhood blindness), and doctors at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London said their vision was “a life-changing improvement”.

Rare genetic conditions mean that the baby’s vision worsens very quickly from birth.

Prior to treatment, they were blindly registered legally, distinguishing only between darkness and light. After the infusion, all parents reported improvements – some of their young children were now able to start drawing.

Further work is underway to confirm early research, which appears in Journal of Lancet Medical.

Another gene therapy for inherited blindness has been provided On the NHS since 2020.

The new work is based on success, which injects a healthy copy of defective genes into the back of the child’s eyes early on to treat serious disease forms.

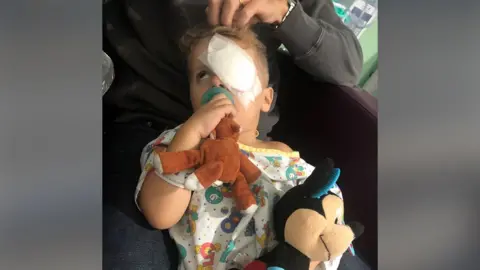

Moorefield Hospital

Moorefield HospitalJace from Connecutt, USA, underwent gene therapy in London when she was two years old.

As a young baby, his parents noticed that his vision was not correct.

“At about eight weeks old, the baby should start looking at you and smiling, and Jace hasn’t done that yet,” said his mom DJ.

She instinctively knew there was a problem and began to look for the reasons why it took 10 months.

After several visits to doctors and many tests, the family was told that Jace suffered from a very rare condition. It is caused by mutations in a gene called AIPL1, and there is no established treatment.

“It’s really shocking,” Jace’s father Brendan said of his first child.

“Of course, you never think it will happen to you, but it ends up finding a lot of comfort and relief… because it gives us a way to move forward.”

The family was lucky enough to hear about experimental trials conducted in London, and only accidentally held a meeting on eye conditions.

His mom said Jace’s surgery was quick and “very easy”. His eyes had four small scars, and a copy of his healthy gene was injected into the retina through keyhole surgery.

These copies are contained in harmless viruses that pass through retinal cells and replace defective genes. The healthy working gene then initiates a process that helps cells on the back of the eye work better and survive longer.

In the first month after treatment, Brendan saw Jace squint for the first time, seeing the bright sunshine playing through the windows of their house.

He said his son’s progress was “very amazing”.

“Before the surgery, we could have lifted an object near his face and he could not track it at all.

“Now, he’s picking things off the floor, he’s dragging his toys, because of something he’s driven by never doing before.”

His parents said it may not be the last treatment he needs in his life, but progress so far is helping him understand the world better.

“It’s hard to emphasize the impact of having a little vision,” Brendan said.

No other choice

Moorefield Hospital

Moorefield HospitalProfessor James Bainbridge, a retinal surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital, helped lead the trial, said early days provide children with opportunities for vision improvement that may be on their development and the ability to interact with people. Have a significant impact.

“Visibility disorder in young children has a devastating effect on their development.

“Infant treatment with this new genetic medicine can change the lives of people most affected,” he said.

Four children from the United States, Turkey and Tunisia are all born in an aggressive form of Leb’s congenital amaurosis, and genetic faults mean cells on the back of the eye – often helping to distinguish light from dysfunction and quickly. Death.

But scientists at University College London have developed innovative programs that involve injecting healthy copies of genes into the eyes.

Unlike traditional scientific experiments, this experimental therapy is provided to families under special permissions when no other option is available.

Children each have treatment for one eye – if treatment has any adverse effects, a measure is taken.

When they perform the procedure, they are between one and three years old and then check their vision in various ways over the next four years, including downward corridors and identification doors.

Given their age, some children find more formal ophthalmic tests challenging.

“Impressive”

According to the doctors at Moorfields, the test results they completed, as well as the improvement reports from their parents, provide “convincing evidence” that all four people benefited from treatment and saw what was expected during normal disease. More expected.

Meanwhile, their eyesight has not been treated and worsened as expected.

Professor Michel Michaelides, consultant ophthalmologist at UCL Ophthalmology Institute, added: “The results of these children are impressive and show the power of gene therapy to change lives.”

The team plans to monitor the child to see how long the results last.

So far, the results have made them hope that early intervention in other childhood genetic conditions can provide the “maximum benefits” and ultimately change the lives of children.