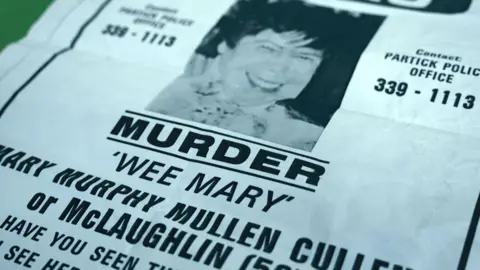

How cigarette butt helped solve 30-year murder mystery

royal office

royal officeMore than 30 years after Mary McLaughlin was strangled, a cigarette butt found in Mary McLaughlin’s apartment provided the first clue to the identity of her killer.

A matching DNA signature was later found in the dressing gown knot used to murder the mother of eleven.

The breakthrough initially baffled cold case detectives because when Mary, 58, was found dead in Glasgow’s west end, the main suspect was an Edinburgh prisoner.

But the governor’s diary confirms serial sex offender Graham McGill was on parole at the time of his grandmother’s murder.

Reports indicate that he returned to his cell within hours of leaving Mary’s home in the early morning hours of September 27, 1984.

fire crown

fire crownA new BBC documentary, Murder: The hunt for Mary McLaughlin’s killerThe story of a cold case investigation—and the devastating impact the murder had on Mary’s family.

Senior forensic scientist Joanne Cochrane said: “Some murders stay with you.

“Mary’s murder is one of the most disturbing cold cases I have ever worked on.”

Mary spent her last night drinking and playing dominoes in the Heindland pub (now the Duck Club), which overlooked Mansfield Park.

Between 22:15 and 22:30 she left the Hyndland Street pub alone and walked less than a mile back to her apartment.

Along the way, she visited Armando’s chip shop on Dumbarton Road, buying churros and cigarettes and joking with the staff.

A taxi driver, who knew her as Wee May, later told how he saw a lone man following her as she walked along the road barefoot and carrying her shoes.

fire crown

fire crownThe sequence of events that led to McGill eventually entering Mary’s third-floor Crathie Court apartment is unclear, but there were no signs of forced entry.

Once inside, he launched a savage attack on a woman more than twice his age.

In an era before mobile phones, Mary was in infrequent contact with her extended family, who lived in Glasgow, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire.

One of her sons, Martin Cullen, visits her once a week.

But when the 24-year-old showed up at the apartment on October 2, 1984, there was no response and when he opened the mailbox he smelled a “terrible smell”.

Mary was found dead inside, lying on her back on a bare mattress.

Her dentures were on the floor and a new green dress she had worn to the bar had been put on from back to front.

Former senior investigating officer Iain Wishart described the crime scene as “particularly brutal”.

He added: “The tragic thing is that she would have looked him in the eyes while he was murdering.”

An autopsy concluded that Mary died at least five days ago after being strangled.

royal office

royal officeOver the next few months, detectives collected more than 1,000 confessions, but the hunt for Mary’s killer hit a series of dead ends.

The following year, the family was told the investigation was closed, but a CID officer urged Mary’s daughter, Gina McGavin: “Don’t give up hope.”

Joanne Cochrane was working at the Scottish Crime Investigation Center in Gatcosh, North Lanarkshire, when she was asked to review evidence from the scene, which had been stored in paper bags for 30 years.

“They didn’t know about DNA analysis at that time,” she said.

“They don’t know the potential of these items.

“They couldn’t have known the value it might have.”

Ms Cochrane said the original investigative team had shown “amazing foresight” in preserving evidence, including cigarette butts.

Google

GoogleMary had 11 children with two fathers and was well known in the local community.

But daughter Gina told the documentary there were tensions as she left her first six children and the five she had with her second partner.

“I thought there was a hidden killer hiding in the house,” she said.

Gina, who wrote a book about her mother’s murder, said she expressed her suspicions to police.

She added: “In 1984, my siblings and I had the same idea.

“It’s one of her own children that was involved or knew something more, but we can’t prove anything.”

By 2008, four independent reviews had failed to establish a suspect profile.

The fifth review was launched in 2014 and the final breakthrough was the passage of New DNA analysis facility On the Scottish Crime Campus.

Previously experts could look at 11 individual DNA markers, but the latest technology can identify 24.

This greatly increases the likelihood that scientists will obtain results from smaller or lower quality samples.

Tom Nelson, head of forensics at Police Scotland, said in 2015 that the technology would make it “possible to go back in time and potentially reignite justice for those who have almost given up hope”.

Samples collected in 1984 included a lock of Mary’s hair and fingernail clippings.

But the breakthrough came with an embassy cigarette butt on the ashtray on the coffee table in the living room.

The cold case team was particularly interested because Mary’s favorite brand was Woodbine.

Ms Cochrane said she hoped technological advances would allow her to obtain tiny amounts of DNA.

She said in the documentary: “Then we got this eureka moment, our eureka moment, where the cigarette butt that didn’t give us a DNA profile now gave us a full masculine profile.

“This is something we have never encountered before and is the first significant forensic evidence in this case.”

It was sent to the Scottish DNA database and compared with the profiles of thousands of convicted criminals.

Results were emailed to Ms Cochrane in tabular form.

She quickly scrolled to the bottom and saw a cross next to the box: “Direct Match.”

Experts said: “This is truly a goosebumps moment.

“It identified a man called Graham McGill and I could see on the form that was issued to me that he had been convicted of a sex offence.

“More than 30 years later, we found an individual that matched the DNA profile.”

police scotland

police scotlandBut the long-awaited breakthrough presented a conundrum because McGill, convicted of rape and attempted rape, was an inmate at the time of Mary’s murder.

Records also show that he was not released until October 5, 1984, nine days after his grandmother was last seen alive.

Former Sheriff Kenny McCubbin is tasked with solving a mystery that makes no sense.

Ms Cochrane was also told more forensic evidence was needed to build a convincing case.

This quest leads her to another “DNA time capsule” – the dressing gown cord used to strangle Mary.

Ms Cochran believes the person who pulled the knot tight was likely exposed to material now hidden within the knot.

Under the lab’s fluorescent lights, she slowly unraveled it piece by piece, revealing the fabric for the first time in more than thirty years.

She said: “We found key evidence – DNA matching Graham McGill – on the knot of the ligature.

“He tied the rope around Mary’s neck and tied a knot to strangle Mary.”

fire crown

fire crownTraces of McGill’s semen were also found on the grandmother’s green dress.

But now-retired Sheriff McCubbin told the documentary that forensic evidence alone was not enough to convict.

“It doesn’t matter what DNA we have,” he said.

“He had a perfect alibi. How could he have killed someone if he was in jail?”

Records are difficult to find as HMP Edinburgh had been rebuilt at the time of the murders and the paperwork had been lost in a pre-computer era.

Mr McCubbin’s quest eventually led him to the National Archives of Scotland in the heart of Edinburgh, where he found the governor’s diary.

One entry changes everything.

Next to the prison number is the name “G McGill” and the initials “TFF.”

Mr McCubbin said: “It was free training, which meant a family holiday weekend.”

The investigative team found that McGill took two days off over the weekend, plus three days of pre-parole leave, and returned to prison on September 27, 1984.

Former senior investigating officer Mark Henderson said: “This is the nugget we are looking for.”

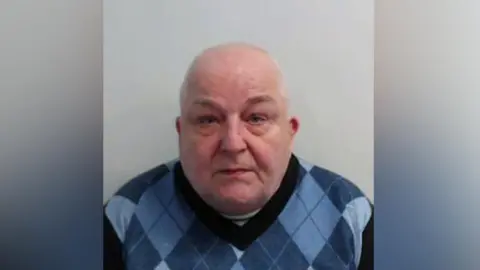

McGill was eventually arrested on December 4, 2019.

At the time, he was still being managed as a sex offender but was working as a manufacturer in the Glasgow area for a company in Linwood, Renfrewshire.

Gina said the news was a relief, adding: “I never thought I would see it in my lifetime.”

In April 2021, after a four-day trial, McGill was ultimately found guilty and sentenced to at least 14 years in prison.

Judge Lord Burns told the High Court in Glasgow that McGill was 22 when he strangled Mary but was 59 when he stood in the dock.

He added: “Her family have had to wait to find out who was responsible for this act, knowing that whoever did it is likely to be at large in the community.”

“They never gave up hope that one day they would find out what happened to her.”