Can elite sport damage women’s fertility?

Getty Images

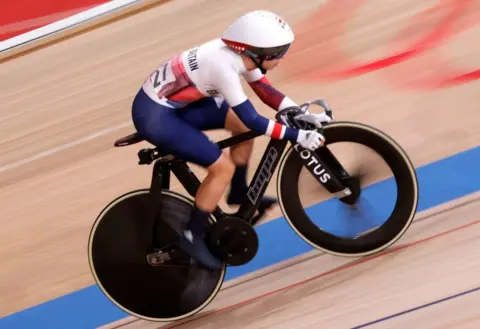

Getty ImagesOlympic gold medalist Dame Laura Kenny is Britain’s most successful female athlete. She has two boys but has also suffered miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies and has long wondered whether the physical toll of elite sport had compromised her fertility. The BBC News Health Team has launched an investigation.

Dame Laura, 32, has dedicated her body to cycling for more than a decade.

“I will give 100% effort every time I train and I will give 100% effort every time I play.

“I took it to the extreme – if I wasn’t sick after a game, I’d be thinking, ‘Did I try hard enough?'”

This sheer commitment pays off on the racing circuit. After winning two gold medals at the 2012 London Olympics, he won two more gold medals at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Later that year, she married cycling star Jason Kenny and welcomed their first child, Albie, in 2017. She went on to win another gold and silver medal at the Tokyo Olympics (to be held in 2021).

But she suffered a miscarriage in November 2021 and five months later developed an ectopic pregnancy, in which the embryo implanted outside the uterus and required emergency surgery.

“Everything shocked me – I went from having complete control of my body to completely losing control,” she told Radio 4’s Today programme.

Lady Laura had never really worried about her fertility before. Getting pregnant with Albie was easy and the pregnancy went smoothly.

But since first speaking out about her loss, other athletes have told her they’ve been through the same thing.

This leaves one lingering question – will elite sport have a damaging impact on the fertility of female athletes?

“Is my body getting exhausted and it’s like, ‘Okay, hang on, there’s no way we can do this?'” she said.

allow Instagram content?

Miscarriage is common. About a quarter of pregnancies end before 24 weeks, and many pregnancies occur at very early stages. Most couples never know why.

But are athletes at greater risk for fertility problems?

Dr Emma O’Donnell, an exercise physiologist at Loughborough University, said the lifestyle of professional athletes places unique stresses on the body.

Elite training burns a lot of calories, so athletes’ bodies are typically lean and muscular with very little body fat.

Menstrual cycle problems, such as missing periods for months or even years, are “very common” if they don’t eat enough to keep up with calorie consumption, Dr. O’Donnell said.

Nearly two-thirds of female athletes experience interrupted menstruation, especially in endurance sports. In sports such as gymnastics, ballet and figure skating, the rate of missing periods is relatively high. In comparison, this proportion accounts for only 2-5% of the total population.

Missing a period may be a sign that ovulation (or egg release) isn’t happening.

How does this happen in the body?

“We’re not 100 percent sure,” Dr. O’Donnell said, but the main idea is that it takes a lot of energy to have a baby, and if the brain thinks there’s not enough extra energy, reproduction will stop.

It begins in the hypothalamus, a small structure in the center of the brain that senses the nutritional status of the body.

Located just below the hypothalamus is the body’s hormone factory, the pituitary gland.

Normally, the glands release hormones that travel to the uterus and ovaries to control the monthly menstrual cycle and the release of eggs, making pregnancy possible.

But if the hypothalamus isn’t happy, the process breaks down and ovulation doesn’t happen.

“If you don’t ovulate, you’re not fertile. You can’t get pregnant because no egg is released,” says Dr. O’Donnell.

The biggest factor appears to be the large number of calories burned while training, which can make it difficult for athletes to eat enough to compensate.

This phenomenon is called relative energy deficit in sport (RED-S) and was first recognized by the International Olympic Committee 2014.

But Professor Geeta Nalgunde, consultant at St George’s Hospital and medical director of Create Fertility, said other factors may also be involved.

Fat in the body helps produce the sex hormone estrogen.

“If this exercise affects body fat levels, then obviously it also affects estrogen levels,” she says.

Psychological stress – possibly from training and competition – can also disrupt the menstrual cycle.

“We do see this in women who are highly anxious,” Dr. O’Donnell said.

She noted that interruptions in menstruation and egg release are the most obvious effects on female athletes’ fertility, but that the problem should be resolved once they retire from competition.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEctopic pregnancy and miscarriage

For those who do manage to get pregnant, things can still go wrong. After the egg is fertilized, it should implant into the lining of the uterus. However, in an ectopic pregnancy, the egg implants elsewhere, usually in the fallopian tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus.

There are approximately 11,000 ectopic pregnancies in the UK each year. Although inflammation and scar tissue in the fallopian tubes increases the risk, it’s not entirely clear why this occurs.

“But in this case, I don’t think there’s a direct link between exercise and an increased incidence of ectopic pregnancies,” said Professor Nalgund, who has treated athletes struggling with fertility problems.

However, she said there is a potential link between excessive strenuous exercise in the first trimester of pregnancy and miscarriage, although more research is needed to confirm.

she pointed A large study in Denmark The study, which followed more than 90,000 women, showed that the more vigorously a woman exercised, the higher her risk. This is especially true for weight-bearing and high-impact exercises.

“If you end up in Laura Kenney territory and become an elite athlete, then you’re at the top of the bunch,” Professor Nalgund said.

But she explained that the findings need to be treated with “caution” because the way the study was designed means there may be other explanations that have not yet been considered.

Meanwhile, a very small study 34 Norwegian athletes No increased risk of fertility problems, including miscarriage, was found.

“We need to do more research on sports, exercise, hormone balance and reproduction,” Professor Nalgund said.

Athletes freeze eggs

Lauren Nicholls played netball at elite level for 10 years and had two children before becoming coach of Premier League champions Loughborough Lightning. She said the conversations players have now about having children are different from the conversations she had with her teammates.

“I know some older players – they’ve frozen their eggs and are making those decisions for their families later,” she said. “Because they’re worried about their careers.”

Juggling being an elite athlete and starting a family has always been a tricky challenge. For women, peak fertility overlaps with peak physical years.

Male athletes also There is no way to avoid fertility problems. Burning more energy than you take in can affect testosterone levels, lead to sperm abnormalities, and even erectile dysfunction.

But for Dr Emma Pullen, a sports researcher at Loughborough University, the lack of clear answers on the impact of elite sport is emblematic of how poorly research is done on everything from fertility to injury risks for female athletes.

Research is “catching up” with the attention paid to men’s sports, she said.

Dr Pullen added: “We are seeing the impact of increasing professionalization in women’s sport and more female athletes than ever before.”

Overall, Professor Nalgunde believes female athletes may face more fertility challenges than other women.

“There appear to be fertility concerns due to the potential effects of (elite sport) on ovulation, including a potential higher risk of miscarriage,” she said.

But it’s unclear how much is too much for elite-level exercise. For now, that’s enough for Lady Laura.

“I feel like the conversation itself is really important because I want people to start talking,” Laura said. “Honestly, I would love it if it was more open.”

Yet the relationship between exercise and fertility affects us all, even if we’re still far from Olympic glory.

How does exercise affect fertility in other people?

Most men and women benefit from exercising and losing weight before trying to conceive – which is known to improve fertility.

For those with hormonal polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), regular physical activity can reduce stress, improve sleep, and make menstrual periods more regular.

But recreational female athletes who train intensively may also have their periods stop or become irregular due to running on an empty stomach.

“It’s not to the same degree, but it’s there,” Dr. O’Donnell said.

Ensuring a balance between energy intake and energy output is “very important to the ovulatory cycle” and key to maintaining reproductive function, she added.

“(Amateur athletes) don’t know how many calories they really need to eat to meet their energy needs.”