‘I feel blessed to get Wegovy weight-loss jab’

British Broadcasting Corporation

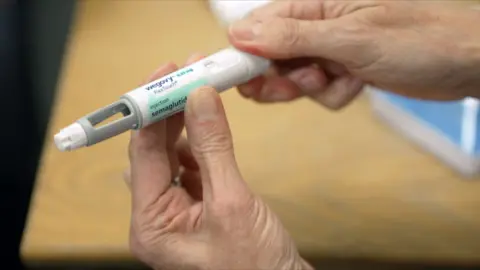

British Broadcasting CorporationRay, 62, from south London, became one of the first patients to receive the NHS weight loss vaccine Wegovy last year, losing 14kg (just over two stone) in five months.

BBC Panorama joined him as he was prescribed his first dose of the drug at Guy’s Hospital in London, where he was told he might need to take it for the rest of his life to prevent weight regain. He said he felt “lucky” to have access to the drug.

But NHS spending watchdog NICE stipulates that each patient can only receive Wegovy for two years. Only a small proportion of the 3.4 million eligible patients in England have access to the drugs.

British Government Leader Professor Navid Sattar Obesity Health Goal Plansaid if everyone eligible had access to the drug immediately, “it would just bankrupt the NHS”.

Being overweight has become the norm, with nearly a third of adults in the UK being obese – double the rate 30 years ago.

Obesity is very bad for your health and it is estimated that treating the complications caused by obesity costs the NHS over £11 billion a year.

Wegovy and another drug called Mounjaro can help patients lose about 15 to 20 percent of their body weight, according to trials.

This kind of weight loss can have a huge impact on health and significantly reduce a patient’s risk of a wide range of diseases, from diabetes to cancer, joint problems and heart disease.

BBC Panorama has secured exclusive rights to the weight management service at London’s Guy’s Hospital, which has begun rolling out Wegovy to a small group of patients who meet criteria (body mass index).body mass index) more than 35 and at least one weight-related health complication.

These include care home worker Ray, who weighed 148kg (23 stone) when he started taking Wegovy in July 2024. He had struggled with his weight his entire life.

Ray needed two surgeries, but doctors said he needed to lose weight first.

With so many patients meeting the criteria, the hospital is prioritizing patients like Ray who need surgery or who have multiple weight-related health complications.

Here, Ray not only receives weekly subcutaneous injections of the drug, but also receives face-to-face support from doctors and nutritionists – advice not always available to those who buy their medication privately online.

They stress that injections don’t do everything and it’s important for patients to change their lifestyle and eat healthier foods and smaller meals.

Ray attended the date with his daughter Sophie, who said it would be “amazing” if he could achieve his target of losing three stone: “I don’t even recognize him. It’s It’s like I have a brand new stone.” “

The drug is currently available through the NHS through these specialist services, mainly in hospitals.

But access to the drug is low.

There are more than 130,000 patients eligible for weight-loss drugs in south-east London, and Guy’s Clinic estimates it can only handle around 3,000 patients.

The weight loss shot that most people know about is Ozempic. It’s in high demand and popular with celebrities like Elon Musk and Sharon Osbourne. In fact, it’s for type 2 diabetes.

Wegovy contains the same ingredient, semaglutide, but in a different dosage.

Semaglutide mimics a gut hormone that sends signals to our brains telling us that we are full. It also slows the transfer of food through the stomach.

In trials, patients using Wegovy lost an average of 15% of their weight, combined with lifestyle and dietary advice.

Experts warn that these drugs should only be taken under appropriate medical supervision because, like all drugs, they have side effects that not all patients can cope with.

These are mostly gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, but there are also potentially serious complications, including pancreatic inflammation.

To help them cope with side effects, patients begin receiving weight-loss injections at low doses and then gradually increase the dose month by month.

Ray was doing well on the drug, eating less, and saw noticeable changes after five months.

When he attended Guy’s Clinic just before Christmas, he weighed 134kg and had lost 14kg, or just over two stone.

He was very happy. “I can’t believe how much weight I’ve lost. Every time my daughters see me, they tell me I’ve lost weight. It’s been such a beautiful journey.”

Ray said he felt “lucky” to be able to access the drug through the NHS, especially now that he is Willow’s grandfather.

Ray said that despite having new holes in his waistband, his pants were so baggy that they fell off his body.

Obesity and diabetes expert Professor Barbara McGowan, who runs Guy’s Hospital’s weight management service, is delighted with the progress of patients such as Ray.

She said most clinicians wanted NICE’s two-year limit to be lifted “because obesity is a chronic disease and we need to manage it long-term”.

Now this may no longer be an issue as a second, more effective drug has been approved by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

Mounjaro has been called the “King Kong” of weight-loss injections because in a pivotal trial, patients lost an average of 21% of their body weight over eight months.

Unlike Wegovy, there is no limit on how long NHS patients can take the drug.

But the NHS will not roll out the drug within 12 years amid fears it could overwhelm services.

Only 220,000 of England’s 3.4 million people are expected to benefit over the next three years.

Professor Sattar from the University of Glasgow said it was a matter of simple economics: “The cost of drugs is still at a level we can’t afford to treat millions of people across the UK. This will just strain the NHS.” Bankruptcy.

He estimated it costs the NHS around £3,000 a year to provide patients with Mounjaro or Wegovy.

So if every eligible person in England could now receive these drugs, the cost would be around £10 billion a year – equivalent to half the entire NHS medicines budget.

Jean, 62, hopes Mounjaro can help her get her weight and health back on track. She showed me a photo on her phone from ten years ago, when she was noticeably lighter and healthier.

“I’m a fitness fanatic. I go to the gym almost every day. I don’t know what happened and why I fell off the wagon.”

She considers her relationship with food “terrible.” “I have a lot of food noise, and I tend to act on it,” she says, using a coined term to describe cravings and preoccupations with food.

Jean qualifies for Mounjaro because she has type 2 diabetes and has been taking insulin injections for five years.

She is worried about the side effects, which are similar to those of Wegovy, but she will be carefully monitored at a diabetes clinic associated with Guy’s Hospital in south London.

Mounjaro helps stabilize blood sugar levels and promotes the body’s natural production of insulin.

After just five weeks on the medication, Joan was able to stop injecting insulin. She’s delighted: “I think it’s Mounjaro, and also willpower – I have to give myself some trust. I think this drug takes the noise out of food and I’m not sitting around thinking about what I’m going to eat.”

After two months on the medication, Jean returned to the gym and had lost more than 3kg (half a stone).

She was disappointed with her weight loss but determined to lose more weight as her dose of Mounjaro increased.

But Jean and the other patients treated by Wegovy and Mounjaro on the NHS are just a minority.

Professor Sattar estimates that more than nine in 10 patients in the UK currently taking weight loss pills pay for them privately.

He noted that obesity rates are highest in socially deprived areas.

“Those who might benefit the most, those who are less affluent and from poorer communities, simply can’t afford this drug. It’s not fair. It’s just the reality of the economic situation.”

But Professor Sattar told me that rising obesity levels could also eventually lead to the NHS being “bankrupt”.

As smoking levels continue to fall, he now believes overweight and obesity are “major drivers of multiple long-term health conditions.”

Both he and Professor McGowan believe bariatric injections have an important role to play and could ultimately lead to wider savings.

Professor McGowan said Ray was a good example: “We treated many of the complications associated with obesity. Ray had pre-diabetes. We wanted to put the condition into remission to prevent all the complications associated with this progressive disease disease.

“He may need joint surgery but losing weight could prevent a lot of complications and ultimately save the NHS a lot of money.”

Professor Sattar said that in ten years there could be 20 weight loss pills on the market, including some in tablet form. He said that as more effective and cheaper drugs become available, they could save the NHS money.

The UK government also believes weight loss pills could ultimately bring wider economic benefits.

A five-year trial in Manchester will examine the wider impact of Mounjaro beyond personal health benefits, including whether it can help some people battling obesity get back into work.

The drugs are not a panacea for obesity, but they offer hope to millions of people after decades of expanding waistlines.

But currently, health services do not have enough resources to treat everyone who is eligible. This means that only a few people like Ray will have access to NHS services in the coming years. The rest must be paid – or not paid.